| A third and more recent appearance of

the Mediterranean signifier in Israeli musical discourse

occurs in the 1980s when musiqa yam tikhonit (Mediterranean

music) or more specifically musiqa yisraelit yam

tikhonit (Israeli Mediterranean music) becomes the

alternative adjective to the genre of popular music that

was until then called musiqa mizrahit

("Oriental music"; see Horowitz 1994). The

evolution of labels used to designate this genre reveals

a change of attitudes by its creators and consumers, the mizrahi

("oriental") Jews. The shift of the 1980s to musiqa

yam tikhonit was intended to differentiate musiqa

mizrahit from other non-European

musics, particularly Arabic music. By adopting this

strategy, both the creators and consumers of musiqa

mizrahit prevented European

Israelis from confusing them with the Arabs whom they

resembled in musical tastes and other aspects of their

culture. Such a distinction also lent legitimacy to musiqa

mizrahit's claims at being truly

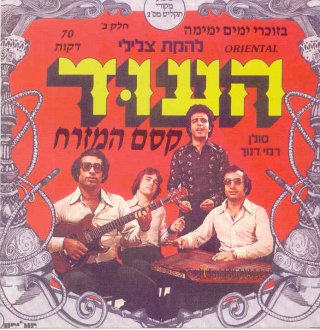

Israeli music. Musika mizrahit is a complex and unique genre within the field of popular music in Israel whose definition is quite elusive.(2) In its initial stages musiqa mizrahit was not specifically Israeli, but mainly Israeli covers of imported Greek, Arabic or Turkish popular music adapted from records, cassettes or radio performances and "made" Israeli by substituting Hebrew lyrics for the original ones. Prominent among these imported musical styles were the songs performed by Greek singers who appeared or established themselves in Israel, such as Aris San, or mellow Mediterranean ballads in the style of the Sanremo festival in Italy. In the 1970s and 1980s, musika mizrahit could be also defined by its public, mostly working class Jews of North African and Middle Eastern origin (called 'edot ha-mizrah, "the Oriental communities"). Rejecting the label 'edot ha-mizrah these Jews consolidated a pan-ethnic sense of identity called mizrahiyut. The rise of the right-wing Likud party to power in 1977, largely on the votes of working-class Easterners, which empowered the mizrahi Jews politically for the first time since the massive immigration of the 1950s, is sometimes perceived as a major turning point in the rise of public attention to musiqa mizrahit. A feeling that their "own" were governing the country, gave the mizrahi Jews a sense of added legitimacy and allowed them to express their ethnicity without endangering their status as Israelis. It was in this social and political context of the late 1970s that the original, authentic musiqa mizrahit fully emerged into the general public scene.

In the 1980s original songs in the more specifically Israeli mizrahi style started to outnumber the covers of foreign songs. Mediterranean music basically became Western popular music with distinctive features: quality of voice emission (specifically Yemenite Jewish singers); use of particular instruments (especially the buzuki), the disproportionate use of the Phrygian mode; and passages in free-rhythm (usually signified by the Arabic term muwwal). The resulting sound of musika mizrahit fluctuates, recalling intermittently the Turkish arabesk, Greek laikÝ, "rocked out" versions of traditional Yemenite Jewish tunes, and ballads in the Sanremo festival style. In the 1990s the fusion of musiqa mizrahit with diverse forms of rock and mainstream popular music brought it to the center of national attention. Musiqa mizrahit, whether adopted whole cloth or originally composed by Israeli composers, became Israeli and not ethnic music. Two major social themes related to musika mizrahit are its discrimination by the Israeli media establishment and its aspirations to become a representation of authentic Israeliness, not just of mizrahi Israeliness. Musiqa mizrahit artists and producers felt rejected by the establishment, particularly by the state-funded media. This rejection was perceived as a de-legitimization of musiqa mizrahit as an authentic form of Israeli popular music. Radio programs dedicated to musika mizrahit, perceived by the producers of this music as "ghettoes" (in itself a loaded term within the Israeli discourse with the clear connotation of harsh discrimination), bear names such as Me'orav yam tikhoni ("Mediterranean Mix"). The new Mediterranean identity of musika mizrahit seems to emerge from this feeling of discrimination. One can best understand this transformation from "Oriental" to "Mediterranean" by analyzing the public airing of the "narrative of discrimination" that developed among mizrahi composers, performers and producers. For example, discrimination became the theme of a relentless campaign by Avihu Medina, one of the most influential composers of this style (wrote over 400 songs) and one of its performers too. To support his thesis that Mediterranean music is "the" Israeli music, Medina stressed four basic related ideas: 1) there is a conspiracy to discriminate against musiqa mizrahit by music editors of radio and television stations; 2) this conspiracy dates back to a period when Israeliness equaled Westerness and this period is over; 3) until the start of his own public campaign there was no protest by musiqa mizrahit artists against discrimination because Eastern Jews are submissive to structures of power due to their education in totalitarian regimes and their lack of experience in open democracies; 4) there is no power now to halt the cultural integration of Israel in the Middle East, and this integration means adopting an Orientalized culture: "Everybody here will be a Middle-Easterner. We go in that direction and those who do not see it are blind". As a result of this analysis, he concludes that musiqa mizrahit is the only authentic Israeli music because it reflects "a synthesis of East and West". It should therefore be allowed slots of airtime in the electronic media that are akin to this status.

The campaign against the alleged media discrimination led, among other developments to the establishment of "Azyt", a non-profit organization dedicated to promote the interests of musiqa mizrahit. From its inception, this organization adopted the Mediterranean signifier as its presentation card: "Azyt" is an Hebrew acronym that stands for Amutat ha-zemer ha-yam tikhoni, "The Mediterranean Song Association". |