The spirtu pront is an extemporized song

contest that develops round a series of arguments created

by the ghannejja themselves in the course of the

session. Each session consists of two to six ghannejja,

but this depends on how many ghannejja will show

interest in participating in that particular session. The

arguments develop in turn in the form of duets and on the

basis of a riposte and counter-riposte. In a session

composed of four ghannejja, the first ghannej

('singer', pronounced 'anney') would be matched

against the third and the second against the fourth. As

soon as the session starts, no one of the ghannejja

can leave or make space for another ghannej; but

he has to stay there till the end of the session. From

this perspective, the spirtu pront has a closed

form in the sense that an ghannej cannot join in

or leave an on-going session whenever he wants to (9).

As mentioned above, the spirtu pront is normally performed in village bars and clubs especially on Sunday mornings. A popular village for the spirtu pront is Zejtun, a village situated in the South of Malta. Zejtun is considered by the ghannejja as the 'cradle' of ghana due to the many ghannejja who originated from it. Every Sunday morning at Zejtun, one will find bars and clubs (mainly political and band clubs) packed with men listening to the spirtu pront. The scene in such bars matches almost precisely the description provided by McLeod and Herndon (1975: 86):

The spirtu pront is also associated with traditional feasts the most prominent being Imnarja celebrated annually on the 29th June. Imnarja is essentially a traditional folk-festival in which the farmers demonstrate their agricultural products at Buskett Gardens. On Imnarja eve, spirtu pront sessions are nowadays being incorporated in a local talent show that would also include band marches, folk dancing and Maltese pop songs. In bars and clubs one will normally find blue-collar male workers either being ghannejja themselves or ghana dilettanti. In more formal public contexts, such as that of Imnarja, spirtu pront sessions will take place in front of mixed audiences composed of people of any age and social class. Women, due to the presence of men, very rarely frequent sessions in bars and clubs. A woman can damage her personal reputation, for instance, by attending to spirtu pront sessions in bars. Maltese society is rigidly segregated along gender lines and therefore, such segregation affects the audience in spirtu pront. Women in bars listening to ghana have in many cases been considered as prostitutes. On the other hand, no one will make such a judgement in more public presentations where sessions are attended by mixed audiences such as during the traditional Maltese feasts of Imnarja or San Gwann (11). The venue in which a spirtu pront session develops is strongly linked to a subtle code about who is likely or unlikely to be present for that session, and consequently the subject of dispute. A spirtu pront session can be divided into three main sections and a coda (12). The first section serves as a prelude for the session. In it, the lead guitarist starts improvising along a motive that he chooses from a 'restricted' repertory of ghana motives (Vella 1989: 38). These motives are popular, not only among the dilettanti of ghana but also with the entire Maltese public. The lead guitarist plays his introductory section accompanied by the strumming of triadic chords provided by the other guitarists. As soon as the former finishes-off with his improvisation he joins the other guitarists on the accompaniment based on the tonic and dominant of the established key. The function of this introductory section is to establish the tonality and tempo for the session. Tonality changes from one session to another, depending on what suits the ghannejja. In the most frequently used 'La accompaniment' (akkumpanjament fuq il-La) the strings of the lead guitar will be tuned to e a d' g' b' e² while those of the second accompanying guitars will be tuned a minor third lower (e f# b e' g#' c#²) except for the bottom string (13). Such tuning is intended to facilitate the technical exigencies imposed on the lead guitarist in his creation of new motifs and variations. In the introductory section a series of rhythmical and intervallic structures are created and developed; this same rhythmical and melodic material is then reiterated in the second section by both the ghannejja and the lead guitarist. The frequent use of syncopation and descent melodic movements, for instance, form part of the formal structure of both the singing and instrumental soloing in the spirtu pront; these are structural elements announced in the introductory section as to establish the style of both ghana singing and playing. The second section develops round a series of alternations between the vocal stanzas of the ghannejja and the instrumental improvisatory four-phrase interludes of the lead guitarist in between each quatrain. Each interlude is known as qalba (literally, 'the turning'). In this section, each ghannej sings a quatrain that in the context of the spirtu pront is known as ghanja (pronounced 'anya' literally 'a song') and then waits till another round. The ghannejja rhyme their quatrains on the rhyming scheme of a-b-c-b. Ideally they should follow the syllabic scheme of 8-7-8-7, but as an ghannej told me: "Nowadays, we give more importance to the rhyme and to the content of the song rather than to the number of syllables in the line". Sometimes it happens that an ghannej opts to intervene immediately with his ghanja as soon as the preceding ghannej finishes-off with his quatrain. This will leave no chance for the lead guitarist to improvise his qalba. This happens due to the urgency of the ghannej to give an immediate reply to his 'opponent'. During the development of the quatrains the lead guitarist may also include light and short bass passages (known as burduni) in order to elaborate on the continuous strumming of the other guitarists. Some ghannejja claim that the burduni put them off. On the other hand, lead guitarists insist that they cannot be creative as much as they wish to be in their improvisations claiming that too much elaborate improvisations will put the ghannejja off. However, instrumental improvisations develop within a restricted framework of more or less 'conventional' unfolding, otherwise the 'ghannejja will look for other guitarists to accompany them' as a renowned lead guitarist told me. The first few lines of each participating ghannej must be general and introductory in nature (Herndon and McLeod 1980: 149) (14). Such lines will normally explain why and how the ghannej has found himself in the place where the performance is taking place. According to Fsadni (1992: 32) the need to introduce a session in this manner evolved in the Sixties as a result of the increasing tendency to tape spirtu pront sessions. Through the introductory lines of the ghannejja the recording could be internally distinguished from other recordings made on the same tape (15). The following are the introductory quatrains of four ghannejja participating in the same session in a bar at Fgura (another southern Maltese village) in 1994: Ghannej A

Ghannej B

Ghannej C

Ghannej D

In more public contexts the first introductory stanzas might also include comments both about the present audience and the significance of the occasion. As the session progresses the build-up of a subject will start to take shape (normally towards the sixth turn) with each pair of ghannejja focusing on a particular subject, adhering to it as much as possible. Renowned ghannejja are able to embellish their quatrains by the use of metaphors, archaic words, proverbs and switching from Maltese to English – such elements make the best ghana. Most of the subjects deal with the ghana environment itself, such as: how many times a particular ghannej has been invited to sing during the past week; the voice quality of the ghannej; his social rapport with the other ghannejja; the endurance of his voice; and how clever and experienced he is in rhyming his quatrains. Nowadays, most of the subjects taken up by the ghannejja are frivolous in nature, more intended to tease the opponent than to harm him, such as in the following lines (taken from the above-mentioned session): Ghannej B

Ghannej D

As well as gentle frivolity, such texts might also symbolize problems in the process of social communication. In this sense, "the meaning of the performance is no longer to state that communication is possible and gratifying, but rather to show in some way that communication is impossible and that the communicative act is frustrating" (Magrini 1989: 63). In more public presentations, such teasing is normally less 'intimate' and more discreet and superficial. The mini environment of the bar is in itself a means of protection to all that discourse which should only be known among friends. The spatial openness in which public performances are held offer no similar protection to that of the bar, with the consequence that members of the audience are normally looked upon by the performers as curious 'strangers', and therefore should not be trusted. The third section of the session is known as the kadenza. In this section each ghannej will 'wind up' his argument with two or more quatrains. Ghannejja of ample talent can extend their kadenza to four and even six quatrains. This might happen either to finish-off their arguments and/or to show bravura. The longer the kadenza the more admiration the ghannej will achieve from his supporters. As performers, the ghannejja seek popularity and prestige with both the public and their fellow ghana dilettanti to the extent that some ghannejja also have their respective supporters. Ample ghannejja will be in demand to sing on television, hotels and other traditional soirées; they get paid for that. Others have been selected to represent Malta in international folk music festivals. Recent directions are the involvement of renowned ghannejja in locally produced musicals, folk operas, CDs together with established Maltese pop singers and even as actors in television plays. Such opportunities have induced certain ghannejja to start disassociating themselves from the environments associated with the spirtu pront in their ventures for new directions where they can better refine and negotiate more acceptable forms of popularity and reputation. They no longer frequent bars and places from where they have received their initial training in ghana, their 'natural' places from where they have attracted the admiration of so many followers. Such situations will continue to confirm Stokes's (1994: 97) assertion that "performance is a vital tool in the hands of performers themselves in socially acknowledged games of prestige and power". A kadenza should make reference to the fact that the argument was not serious, or that the singers were only joking. From the musical point of view, the kadenza is characterized by an increase in the rate of harmonic change (I-IV-V7-I). The following is an example of a kadenza taken from the above session: Ghannej A

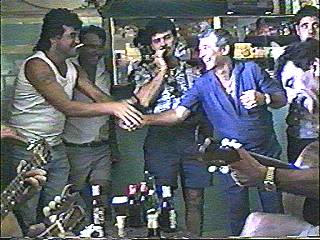

The kadenza is then followed by a short instrumental coda (I7-iv-I). As soon as the coda starts the ghannejja shake hands as if to show that what has been said should not be taken seriously by neither the participating ghannejja nor the audience.

The ghannejja should be able to rhyme their quatrains. A well-constructed quatrain, sung in the right time, should always achieve the appreciation of the listeners. While singing his ghanja the ghannej should be careful to keep with the tempo of the accompanying guitars. Among the various session I came across there was a particular one in which one of the participating ghannejja was a young ghannej who seemed to be in his apprenticeship. He had problems keeping within the established tempo whilst at the same time rhyming his quatrains. Both the lead guitarist and one of the performing ghannejja drew the trainee's attention to this fact at several moments of the performance; singing in time with the established tempo was an important factor for the success of the session and therefore it had to be tackled seriously and with urgency. Similar cases may shed more light on the importance of the learning process as a useful source of musical theories and concepts. Although these are unwritten, they will still be regulating the music of the oral musical culture under investigation. |