Sephardi men, who dominated text writing and transmission in their communities, shaped the image of their singing women as threatening "others" that have to be controlled. The rabbinical literature explicitly treats this subject. A fresh reading of these texts reveals that the singing of folk songs was one of the most powerful means for the expression of female self-identity in traditional Sephardi societies. Rabbinical opinions on the singing of Sephardi romances and canciones by women are a relatively neglected source of study. A few years ago I published texts by Sephardi rabbis from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries that treat this issue (Seroussi 1993). Hereby is the translation of some of these excerpts:

Religious songs arose the communion with God, but the songs that women sing, with their frivolous lyrics and dirty language, cause the separation between soul and body and even if [the lyrics] do not use corrupted words, all these are lyrics without substance, and people of low stature are attracted by the lyrics of these cheap songs, and they loose their soul, and about them the prophet said: "Spare Me the sound of your hymns, and let Me not hear the music of your lutes" [Amos 5:23].

It is forbidden [for] women to rise their children with lascivious songs and lustful lyrics, because these songs profane body and soul. And the mind of the woman becomes light and [she] interprets these lyrics about forbidden loves as if they referred to herself and she imagines that she actually participated in the plot and from this she falls into profane thoughts, as the snake that engenders the flying serpent, the leper of prostitution. And moreover, when the woman gets used to utter these lascivious songs from her mouth, she leans towards empty words and to defiling her mouth. And there are women who talk to their little children blasphemies as if they were playing with them. Damned the name of those [women] who do such a thing, because this shows that they are attracted to the evil of prostitution and they cause a malign epidemic because when their children grow up, they learn to listen and to say the same dirty utterances and desecrate their mouth without being aware of it. For this [reason] the woman should care for each word she utters so that these will be pious and graceful words, pleasant and exquisite words.

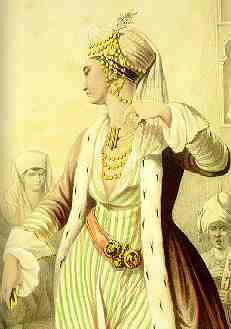

Whoever rises his hears to listen to innocuous words [devarim betelim] and to songs of women, and even [to songs] of men that are not pizmonim (religious songs), causes damages to himself. These texts reflect the rabbis’ awareness of their women’s extensive singing activities and their inability to stop them from doing so. Moreover, in the literature one finds few cases of Sephardi and Oriental Jewish women who not only performed but also created in the field of poetry and song. In Spain and around the Mediterranean, Sephardi women even composed songs in the exclusively masculine field of religious poetry in the medieval period (Haberman 1981). Fleischer (1984) assumes that the wife of Dunash ben Labrat, the poet who is credited with founding the medieval Spanish school of Hebrew poetry in the tenth century, was a poetess. Another striking example are the religious poems (piyyutim) by a Moroccan Jewish poetess from the eighteenth century (Chetrit 1980, 1993). The existence of assertive Sephardi women performers is exemplified by yet another rabbinical responsum. The text is part of a case included in Moshe yedabber (fol. 57a) by Rabbi Moshe Israel of Rodhes (died 1782) described by Angel (1978:32-33): While selling their wares in the gentile district outside the city of Rhodes, two Jewish merchants witnessed a group of non-Jewish men and women as they were leaving the scene of a social gathering, playing drums and trumpets. Among the group were two Jewish women, who were singing and rejoicing along with the others. The two merchants reported the incident to the Chief Rabbi who, in turn, summoned the women to a meeting at which he warned them about their inappropriate conduct. The women replied that while they did indeed go to gentile’s parties, they did so solely in a professional capacity, not to socialize with the non-Jews, but to sing for pay. Moreover, they assured the rabbi, they were guilty of no wrong-doing, as they did not eat the gentile’s food or even drink their water. Despite these assurances, the rabbi told the women that their conduct was improper and that they must discontinue working in such capacity. This story has a second part in which one of the female singers curses in public one of merchants who accused her in front of the rabbi, the merchant curses her back, and the singer’s grandson, "a strong, brutish person", threatens the merchant. From this story we learn that semi-professional Sephardi female singers used to perform for gentiles at an advanced age (the singer is our case is obviously a grandmother). Postal cards from Saloniki dating from the early twentieth century portrait some of these Sephardi female ensembles. There is also evidence that professional Jewish female singers were active in North Africa even in earlier times (Jones 1987:73-74).

|